Published : 2021 || Format : print || Location : Colombia ☆ ☆ ☆ ☆ ☆ What was it about the country that kept everyone hostage to its fantasy? The previous month, on its own soil, an American man went to his job at a plant and gunned down fourteen coworkers, and last spring alone there were four different school shootings. A nation at war with itself, yet people still spoke of it as some kind of paradise.. Thoughts : Infinite Country follows two characters - young Talia, who at the beginning of this book, escapes a girl’s reform school in North Colombia so that she can make her previously booked flight to the US. Before she can do that, she needs to travel many miles to reach her father and get her ticket to the rest of her family. As we follow Talia’s treacherous journey south, we learn about how she ended up in the reform school in the first place and why half her family resides in the US. Infinite Country tells the...

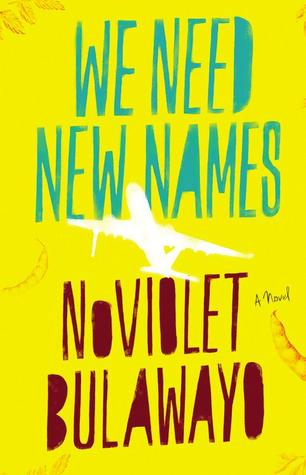

Last week, I started reading We Need New Names by NoViolet Bulawayo, after hearing from many about how good it was. I had read a few African literature before, though, as the main character in We Need New Names, Darling, points out, Africa is not one country but a continent of fifty-some countries.

When I started reading the book, I was disappointed by how slow I was having to read it just to understand what the narrator was trying to say. Rereading chapters, and sometimes, restarting a book after already reading a couple of pages or chapters, is very normal for me. That helps me reorient myself in the book's atmosphere and relax into the book's world. With We Need New Names, restarting did help, but the writing continued to be a tad difficult. Darling had only done a few years of school, and her English, while better than that of her friends and family, was still very shaky and could use a lot of refinement. As We Need New Names is narrated by her, it is written mostly in broken Zimbabwean English.

I'll admit - it took me a good while to feel invested in the story. Darling's English is not one that I am familiar with. Reading the book felt like listening to someone speak in a thick accented English that I was hearing for the first time. But as I continued reading and warming up to her, I began to understand her much better than I would, had she spoken perfect English. Her vernacular English was part of her identity, her persona, and taking that away from her, would take away a relatable aspect of her personality. By the end of the book, when she had settled in the US, she was speaking very good English - she had learnt a lot by then and excelled in the language, that she was able to speak it commandingly.

There are plenty of books out there written in the vernacular English, but not many of them make a name in mainstream media. Maybe they are a little challenging to read? Maybe the sprinkling of phrases in other languages throughout the book take away some of the enjoyment that may come naturally otherwise? Or maybe, vernacular English just doesn't feel like correct English?

One of the things that disappoint me so much about books set in India is the language. Quite a few books I've read are written as if the narrators have taken a couple of Masters degrees in the English language. Very few of those characters are even introduced as being experts in the language. I remember reading a book set in a rural village, the last place on earth where people even speak English. And yet we had characters waxing poetic all the time. It felt very surrealistic. I understand the need for authors to put forward their best language skills in the books they write. After all, most authors want to be internationally acclaimed. NoViolet Bulawayo, however, reminded me that one can still write books in broken English and get the point across globally.

When I started trying to read more around the world early this year, I was especially looking for books like this one, where there is more of a cultural representation in the writing. Frangipani also was written the same way - a lot of Tahitian delights spring out from this book. I remember raving a lot about it then, but I only realized now that the writing was the main reason I loved the book so much. Vernacular writing becomes more important when the book is written in first person. Most people don't speak like Shakespeare did. Everyone has their own way of speaking, which generally includes slangs. Getting that manner of speaking into a book makes the book more personal, more genuine. Even if there is an initial struggle trying to get into the book, the patience is usually worth it. Wouldn't you expect a book with a 5-year old narrator to speak like one? So why not have a Cambodian character speak to us in his regional natural manner of speaking?

This post is part of my Armchair Traveler project.

Comments

However, I've read books in vernacular set in places like Ireland or Scotland, and it was impossible for me to follow along. It was just too different from the language I am used to.